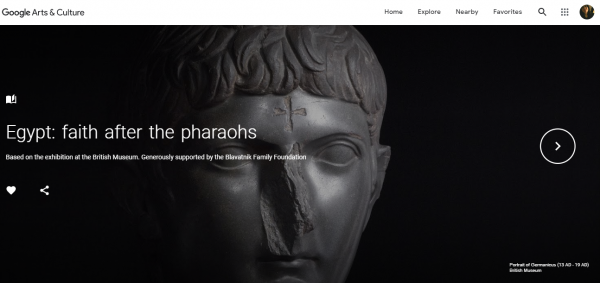

Egypt: Faith After the Pharaohs is an online exhibition hosted on the British Museum’s page on Google Art and Culture platform. The exhibition’s landing page marking its starting point features one of its most provocative objects; a close-up of the bust statue of Germanicus, great-nephew of Augustus (in Alexandria, Egypt) with a cross engraved on his forehead around 300 years post-creation in a Roman empire now dominated by Christianity. The choice of welcoming object is very telling of its overarching theme featuring periods of spiritual turning points and transitions.

Egypt: Faith After the Pharaohs is the digital and more concise version of the physical exhibition, with the same title hosted by the British Museum in London during the years 2015-16. Alike its huge physical predecessor, the online exhibition, presents a smaller collection of 17 objects carefully curated to ensure diversity in materials, historic eras, and religious significance. In this richly diverse exhibition, one gets an opportunity to browse through objects of remarkable significance to anyone interested in archaeology, ancient Egypt, history in general and history of religion and mythology in specific, and/or any/all of the three monotheistic religions. The exhibition includes a wide array of objects ranging from precious and rare documents to everyday artefacts: an image of a bronze head of Augustus alongside an early draft scripts from the Torah in the handwriting of Maimonides, in addition to jewelry, furniture, textiles, sculpture, ceramics, manuscripts and fragments of papyrus.

Browsing through historic objects in a digital space is a relatively new experience. Amidst a time of fast development in the field of cultural heritage digitization and the associated technologies allowing for complex 3D displays and interactive navigation within virtual spaces, Google has introduced its own exhibition platform. Allowing for a wide viewership base and easy access and navigation, Google Arts & Culture (formerly Google Art Project) has been defined as an online platform through which internet users can access high-resolution images of artworks/artefacts housed in the museums partnering with this initiative. The platform allows the museums to group the images in curated sets of collections and displays them in the form of online exhibitions. The project was launched in 2011 by Google through its Google Cultural Institute initiative, in cooperation with 17 international museums, including the British Museum.

Through this online platform, Egypt: Faith After the Pharaohs offers an intuitive navigation that allows the viewer to horizontally navigate through the collections in a motion that simulates a walk through a timeline. The arrows pointing to the right hand-side invites the viewer to start exploring the exhibition. The chronological navigation of objects commences with the conquest of Roman leader Augustus up to the establishment of the Ayyubid dynasty by Salah al-Din (Saladin). A bronze head of Augustus marks the earliest object in the display whereas a map commissioned by the Abbasid caliph Al-Ma’mun is the latest. One disadvantage of the exhibition’s chosen is its starting point, which succeeded early pivotal religious milestones in the history of Egypt, such as the challenging of ancient Egypt’s god Amun by Akhenaten in the 1300s BC or the early rise of Judaism in Egypt, and including other relevant objects from the British Museum’s collections.

The exhibition keeps things simple by displaying one-to-two image(s) of artefact(s) per slide allowing for more white space on the screen and a more relaxed browsing experience. The information layer takes many shapes and forms. The interpretive labels marking the entry points of the exhibition, starting with the title label and section labels mark the four different sections in the exhibition. The orientation label on the second slide, offers a one-paragraph description of the collections displayed and the scope of the exhibition. Forward and backward navigating between slides is achieved through back and forth arrows that serve as wayfinding and orientation signs in this virtual space. In the following slides, section labels such as ‘Roman Egypt: religion and empire’, ‘The arrival of Islam’, and ‘Egypt: Mirror to the World’ are both catchy and explanatory. The group labels, on the other hand, are designed to individually provide necessary information about the stage in history to which the exhibited objects in the slide belong to, and to collectively narrate the history of religion in Egypt during the period covered by the exhibition. At first glance, one could easily think that the exhibition is lacking identification labels, however, the curator has included captions with very brief text in a smaller font below each image of objects and offered elaboration (on the origins of the object, the materials with which it is made, physical dimensions, etc.) on external pages referred to by hyperlinks. Within the information layer, it was surprising to notice the lack of information in the captions about the origins of the objects and how they were acquired by the British Museum. At a time where repatriation of heritage objects is a growing debate, similar lack of transparency is unfortunate.

One major gain from visiting any form of digital exhibitions over its physical counterpart, would be the capacity to make use of modern technology to leverage the viewership experience of the objects in display, a process that one would traditionally only be possible from behind a glass case. Despite its reliance on simple 2D images, this online exhibition enables the viewer an undistorted zooming experience of the objects (thanks to the set of high-resolution images upon which this exhibition is based), allowing them to discover a magnificent level of details that is impossible to explore otherwise. Supplementary multimedia is another grace which enables adding another information layer to the exhibition through embedding of short (3-5 minutes) captioned commentary videos of interviews with historians, scholars and museum curators elaborating on the theme of the selective objects.

Among the many exquisite objects, the furniture fittings depicting the cities of Constantinople, Antioch, Rome and Alexandria stand out as especially intriguing. The four silver and gold figures of female goddesses, represent the 4 most important cities of the Roman world in the 4th century. The level of details showing the Alexandrian goddess wearing a crown depicting the city walls, towers, and gates; she carries fruit and sheaves of wheat symbolizing the bounty shipped up the Nile and exported through the city’s harbour is absolutely fascinating. Given the actual size of the objects (185 X 69 mm), it would have been impossible to admire all the details if not for the new technology.

Overall in my view, the exhibition is a success. It has done a decent job in further curating objects for the purpose of display in a virtual space from a larger set of objects in pre-curated physical exhibition. The selected objects are unique, rich and telling of the underlying theme and scope intended of the exhibition. The historical narration conveyed through the different layers of labels is accessible to a wide range of audience and the complementary commentary interview adds an authoritative dimension to the information layer and enriches the viewership experience. It is unfortunate that this (and other) online exhibitions are not very well advertised on the museum’s website.

References:

Barnet, Sylvan. “Writing a Review of an Exhibition.” In A Short Guide to Writing About Art, 143-155. New York: Pearson/Longman, 2005.

The British Museum. “Collection Online.” Accessed February 10, 2020. https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/search.aspx

The British Museum on Google Arts and Culture. “Egypt: Faith After the Pharaohs.” Accessed February 1, 2020. https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/egypt-faith-after-the-pharaohs-the-british-museum/IQJS2q6UTAaFJg?hl=en

The British Museum on Google Arts and Culture. “Furniture Fittings Depicting the Cities of Constantinople, Antioch, Rome and Alexandria.” Accessed February 11, 2020 https://g.co/arts/4EwC1NCykap6wZDW9

Florence Waters, “The Best Online Culture Archives.” The Telegraph, February 11, 2011.

Frankfort, Henri. “The Egyptian Gods.” In Ancient Egyptian Religion: An Interpretation, 3-25. New York: Harper, 1961.

“Furniture Fittings Depicting the Cities of Constantinople, Antioch, Rome and Alexandria.” The British Museum on Google Arts and Culture, accessed on February 11, 2020 https://g.co/arts/4EwC1NCykap6wZDW9

Navarrete, Trilce. “Digital Heritage Tourism: Innovations in Museums.” World Leisure Journal 61, no. 3 (2019): 200-214.

Serrell, Beryl. “Types of Labels in Exhibitions.” In Exhibit Labels: An Interpretive Approach, 21-36; 233-236. London: Rowman and Littlefield, 1996.

Waters, Florence. “The Best Online Culture Archives.” The Telegraph, February 11, 2011. Accessed February 8, 2020. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/8296365/The-best-online-culture-archives.html

Learning Significance